Foreign Export Credit Competition Continues to Intensify as U.S. Competitiveness Wanes

Amidst a growing debate about the future of the U.S. Export-Import (Ex-Im) Bank, along comes fresh evidence that foreign export credit competition continues to intensify even as U.S. competitiveness at providing export credit assistance continues to weaken compared to leading competitor nations. The 2014 Report to the U.S. Congress on Export Credit Competition and the Export-Import Bank of the United States (released Wednesday, June 25) documents clearly how virtually all U.S. competitors are investing significantly more as a share of their GDP than the United States in providing export credit assistance in the form of loans and guarantees to help foreign buyers purchase their nations’ products and services.

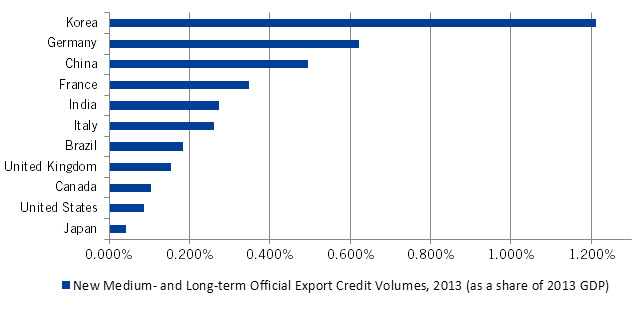

As the figure below shows, virtually all the world’s leading export economies—including the ones which U.S. manufacturers compete most closely against—invested more in new export credit assistance as a share of their economy than the United States in fiscal year (FY) 2013. For example, China’s investment in new medium- and long-term export credit assistance exceeded the United States’ by 5.7 times in FY 2013, while Germany’s level outstripped the United States’ by over 7 times. Korea invested 14 times as much as the United States in export credit assistance in FY 2013.

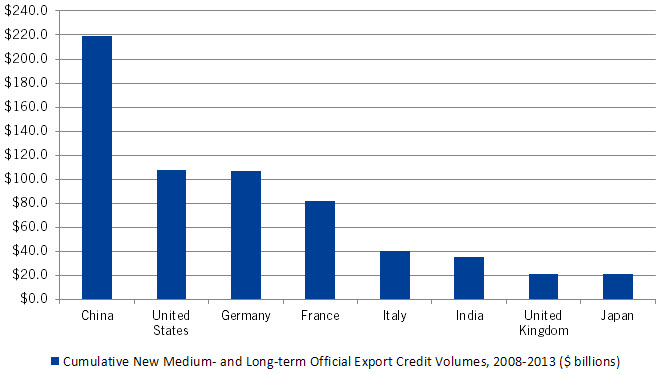

And those figures only reflect FY 2013 new medium- and long-term official export credit volumes. Examining cumulative investment over the past six years (FY 2008 to FY 2013) reveals that China has invested twice as much in new medium- and long-term export credit as the United States in current dollars, and almost four times as much as a share of GDP over this period (see following chart). And while the United States and Germany have committed roughly the same amount of export credit assistance over this period (the United States investing $108.2 billion to Germany’s $107.1 billion), the reality is that Germany’s relative investment is almost five times larger than the United States’ because U.S. GDP is 4.6 times greater than Germany’s. Simply put, these countries are investing substantially more as a share of their economy to support the exports of their companies’ products and services.

More than this, the 2014 Report to the Congress on Export Credit Competition and the Ex-Im Bank reveals that unregulated export credit competition has significantly expanded. In fact, whereas fifteen years ago 100 percent of countries’ official export credit assistance operated under international rules established through the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) to ensure that companies could compete on free-market factors such as price and quality rather than on aggressive government financing, in FY 2013 that figure plummeted to 34 percent. In other words, only $97 billion of the total $286 billion in new export credit issued by countries worldwide last year was governed by global rules. Much of this growth in unregulated credit came from the “BRIC” countries—Brazil, Russia, India, and China—which are not subject to the OECD framework regulating export credit and often aggressively use export credit to support exports from their state-owned enterprises. As the Financial Times notes, these figures “show how the rise of emerging exporters such as China—which have not signed up to international rules designed to limit export credit—threatens a new form of mercantilism as countries use cheap finance to boost their industries.”

At the same time, the Ex-Im report to Congress noted that “the appetite of commercial banks for long-term projects [has] continued to diminish since the implementation of Basel III and other banking reforms.” With liquidity sources for certain projects remaining scarce, the report emphasizes that export credit support has actually become more necessary to fill gaps in the trade finance marketplace. That’s just another example of how America’s Ex-Im Bank does not compete with private sector lenders but rather acts as a “lender of last resort,” responding to a market failure by providing export financing products that fill gaps in private trade financing.

In short, the latest data convincingly show that export credit competition is not going away—in fact, it is increasing—and demonstrates the folly of those who would advocate that the United States unilaterally disarm from providing export credit assistance. That would be disastrous for U.S. manufacturers. If the United States does not provide export credit assistance to foreign purchasers of U.S. products and services in situations where private sector lenders are unable to do so, the simple reality is that in many cases these would-be buyers will turn to European or Asian manufacturers, getting the export credit assistance required from a European ECA or from the Chinese Export-Import Bank, and so sales of U.S. Boeing jets would be replaced by sales of Airbus jets, or sales of GE locomotives replaced by locomotive exports from Germany’s Siemens or China’s CSR.

With Congress set to vote on reauthorization of the U.S. Export-Import Bank this Fall (the Bank’s current authorization expires on September 30), the reality is that a vote against the Ex-Im Bank is a vote against American manufacturing.

Editors’ Recommendations

April 1, 2015