The Sad Reality Behind Foreign Direct Investment in the United States

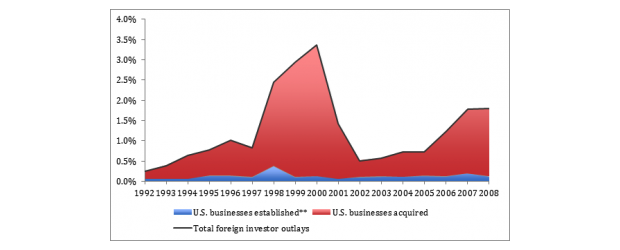

Foreign Direct Investor Outlays in the United States as a share of Gross National Product, 1992-2008* (Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis)

One rebuttal commonly used against those of us worried about the large and persistent U.S. trade deficit is that a trade deficit implies a “capital account surplus.” In other words, a trade deficit must be offset by inflows of funds, and those funds are sometimes (although far from always) used to finance investment in the U.S. economy. One big part of these inflows is foreign purchase of U.S. debt, such as corporate securities or Treasury bonds that finance government spending. The other big part is foreign direct investment (FDI), which is the inflow of foreign funds used to control (i.e. own) business assets within the United States.

While the economic benefit of the financing of U.S. debt by foreign entities is hotly debated, the inflow of FDI is often touted as a sign of continuing U.S. economic strength, given that, at first blush, the influx of foreign dollars appears to support investment in companies in the United States and thus million of American jobs. It is important to note, however, that there are in fact two kinds of FDI, and each has different consequences for the American economy. The first kind is FDI that is used to establish new U.S. businesses—known as “Greenfield” investment—and this is nearly unequivocally good, as brand new establishments in the United States do indeed qualify as new investment and thus create brand new American jobs. The second kind is FDI that is used to acquire preexisting U.S. business (those that were previously owned by American entities) and the benefits of this sort of FDI is much more ambiguous. Although the U.S. economy may benefit if the new foreign owners run the American business much more efficiently, the investment and jobs benefits are far from certain, as the business and those jobs are not new, but rather had existed even before the foreign acquisition occurred. Indeed, foreign acquisitions are far more risky for the U.S. economy given that they are effectively ceding control of U.S. businesses to foreign entities—and along with that control, acquisitions may also cede the knowledge and innovative capacities of those businesses, effectively boosting the competitiveness of foreign multinational corporations that directly compete with American corporations, particularly if those corporations are domiciled in mercantilist nations like China.

So, which kind of FDI dominates, Greenfield FDI or acquisitions of existing businesses? Unfortunately, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) discontinued its survey of Greenfield investments in 2009, and thus the latest available data are for 2008. However, the data from 1992 to 2008 paint a bleak picture, as the figure above shows, and it is likely fair to assume that not much has changed in the past three years.* Acquisitions constituted on average 86 percent of all new foreign investment outlays in the United States from 1992 to 2008, and Greenfield investment constituted just 14 percent.** Moreover, in 2008, Greenfield investment was just 7 percent of new FDI outlays. The rate of change is no better: from 1998 to 2008, acquisition investment grew at a rate of 2.9 percent per year, while Greenfield investment had a growth rate of (negative) -6.1 percent per year.

This means that the story of the economic costs of the U.S. trade deficit being counterbalanced by the economic benefits of surpluses in capital inflows is flawed. In reality, much of inward FDI in the United States is not the jobs and investment boom that many make it out to be, and instead presents another facet of American decline, as U.S. businesses cede assets (both tangible and intangible) to foreign competitors. Just to be clear—the United States should welcome Greenfield FDI, but most FDI is not Greenfield and, as a form of investment, is fundamentally no different than foreign purchases of U.S. treasuries.

*Foreign direct investor “outlays” differ slightly from the FDI “financial flows” used in the BEA’s international transaction accounts in that financial flows are restricted only to funds flowing across the U.S. border whereas outlays are restricted to “new” funds. For example, outlays include indirect acquisitions and establishments by a U.S. business that is already foreign owned, while financial flows exclude this, because the funding is new but does not flow across the border. Conversely, if a foreign investor provides additional funding to the U.S. business it already owns, then it is included in financial flows but excluded from outlays, because the funds flow across the border but are not new. That said, because we are only interested in new foreign dollars when it comes to Greenfield investment and because the correlation between the two series is extremely tight (+0.95), the data difference is of no consequence.

**The U.S “businesses established” share of foreign direct investor outlays acts as a close proxy for Greenfield investment, as the businesses established data accounts for the creation of new legal entities by foreign direct investors, which may in some cases include establishment investment that is not traditionally considered Greenfield, such as the creation of a new legal entity when a foreign direct investor purchases real estate. However, the bias in this case is likely upward, and thus true Greenfield investment share of outlays is likely even lower than these figures show.

Editors’ Recommendations

January 28, 2015

An Economics for Evolution

January 20, 2015