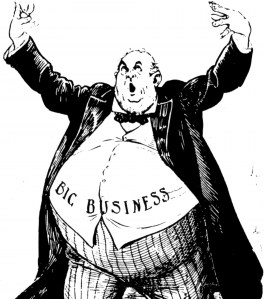

In Praise of Big Business: Part 2 (Why Government Policy Should be “Size Agnostic”)

In my blog last week, I drew from our forthcoming book Innovation Economics: the Race for Global Advantage (Yale University Press) to show how the current “small business is better” obsession is misguided and that in fact big business is the key driver of U.S. economic prosperity and competitiveness: it pays higher wages, is more productive, produces proportionally more patents, does more R&D, exports more and is a critical driver of job growth.

Despite these clear benefits, the narrative in Washington is that Main Street mom-and-pop businesses are the backbone of the American economy and deserve special privileges. And of course many organizations, most prominently the National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) which claims that it is “The Voice of Small Business," play this for all its worth to extract “small business welfare” from the government. The NFIB portrays itself as the defender of the companies that create jobs and wealth and woe to any politician who dares to threaten these American-as-apple-pie economic engines. But while the NFIB’s membership may include a smattering of high-growth, innovation-based firms, the lion’s share are small Main Street firms that are almost completely dependent on big business or high-growth entrepreneurial companies for their well-being. And NFIB fights for special exemptions, incentives and subsidies to these companies. This list of these entitlements is long and deeply ingrained in Washington.

Small businesses are routinely exempt from regulatory burdens large companies face. These include provisions regarding health insurance, paid family leave, notice to workers who are being laid off, and reporting job related accidents. For example, in the recent health care reform law that the Supreme Court upheld yesterday, employers with 50 or more full-time employees will be taxed if they don’t offer health insurance that covers minimum value. Whether you love or hate “Obama care” the law should be the same: either no business must provide health insurance to their workers or all should.

We even have a law – the Small Business Regulatory Fairness Act of 1996 – that seeks to ensure that large firms face a bigger regulatory burden than small firms. The Act seeks to among other things to:

- simplify the language of Federal regulations affecting small businesses;

- develop more accessible sources of information on regulatory and reporting requirements for small businesses;

- create a more cooperative regulatory environment among agencies and small businesses that is less punitive and more solution- oriented; and

- make Federal regulators more accountable for their enforcement actions by providing small entities with a meaningful opportunity for redress of excessive enforcement activities.

But all regulations, whether they affect big or small business, should try to do this. Why just give small businesses a regulatory environment that is solution oriented, for example?

There are surely some cases where there might be cheaper ways for small businesses to comply with regulations, but the notion that a company should be exempt from a regulation— and by definition can impose costs on society – while a company with more workers is not, distorts the economy. If a regulation makes sense it should makes sense for all business. If it doesn’t make sense, it shouldn’t make sense for all business, not just small business.

Small businesses also get tax breaks that large businesses do not get. The corporate tax rate on the first $50,000 of income is 15 percent, while on revenue above $18,333,333 it is 35 percent. Small corporations with less than $5 million in receipts are exempt from the corporate AMT. It is routine for Congress when passing special bonus depreciation rules to limit them to small business (to their credit the Obama Administration and Congress did extend bonus depreciation to all sized firms during the recession). Moreover, many cities and states have special tax exemptions for small business.

Small business even get preferences in government contracting, even though by definition this costs taxpayers more. SBA’s 8(a) Business Development Program helps small business get government contracts. The Obama administration has even a set a goal of giving 23 percent of prime federal contracts to small business. We see this in most areas of government policy. For example, telecommunications policy. James Murray’s wonderful book Wireless Nation details the massive amount of gaming and fraud involved in the early days of FCC spectrum auctions because the FCC required that a certain share of spectrum be allocated to small companies. It took years and probably hundreds of millions of dollars to rectify that mistake and build a national wireless system with players large enough to invest in truly national networks. We still see this today where the federal government favored small wired and wireless broadband carriers in programs like the BTOP grant program and in the FCC’s Office of Communications Business Opportunities. And many states and cities also favor small business in procurement. The result is many “front” companies that exist only because they know government agencies have to allocate a certain share of contracts to small companies. There is also fraud and gaming in these preference programs.

We even have an entire federal agency devoted just to small business – the Small Business Administration. And their principal activity is to provide more generous financing for small business through its 7(a) loan program and others. And SBA’s Office of Advocacy is dedicated to making sure that small companies get a better deal than large companies.

This is not to say that all programs focused on small business are unfair and wasteful.

The federal SBIR program, which allocates a small share of federal research budgets, has helped small innovative growth companies get off the ground. The NIST Manufacturing Extension Partnership plays a critical role in helping small manufacturers become more innovative and productive. And there are others. But the distinction is these kinds of programs are focused on a particular kind of small business – small businesses that have high growth “gazelle” potential and/or that play critical roles in ensuring U.S. global economic competitiveness. Thus, while federal policy should be size agnostic – the default position should be that all firms regardless of size should be taxed, regulated and purchased from on a level playing field unless there is a compelling reason to deviate from this – it should not be completely agnostic. To the extent that federal policy can help firms that are facing tough competition in in global marketplaces (e.g., traded sector firms) and/or that have high growth potential (e.g., entrepreneurial gazelles) more than firms (small or large) that are not, that’s fine. To the extent the policy is focused on helping small business become more productive that’s probably fine too. But tax, regulatory, procurement and other policies that are at best zero sum games that just seek to exempt small firms from obligations larger firms face distorts the economy toward a less productive, innovation and competitive one.

If we want to restore American competitiveness it’s time to rethink programs designed to help Main Street small business broadly, as opposed to the subset of small manufacturers or high-growth entrepreneurial companies. Why enact bonus depreciation only for small firms? The sum of these policies results in smaller, less productive, lower-wage non-traded firms being a larger share of the economy than they would be otherwise. But the policies survive, and even thrive, since it’s a way for both parties to be seen as business friendly even though doing so is taxpayer, worker and consumer unfriendly.

So what should we do? Let’s start by embracing “Size agnosticism”. Second, governments should eliminate most of the preferences given to small business. Let’s make small firms face the regulatory requirements that large firms face, such as the Family and Medical Leave Act and the health care reform act. Let’s eliminate procurement set-asides for small business. Let’s tax corporate income at the same rate (ideally lower) regardless of size of firm (e.g., the level of income). Let’s make all companies pay the same application fees for government programs, like applying for a patent. Let’s repurpose the Small Business Administration away from providing assistance for mom-and-pop businesses and toward providing help for small manufacturers and high-growth start-ups.

But, wouldn’t being size agnostic mean a lot fewer small businesses and jobs? This after all is what groups like NFIB will assert in order to scare elected officials. To be sure, it might mean fewer small businesses. But since when is government in the business of picking winners based on size? To take a hypothetical example, if consumer choice dictates that 80 percent of home improvement supplies should be sold by large firms (e.g., Home Depot, Lowes, etc.) then that maximizes consumer welfare compared to a world where government favoritism leads small hardware stores having 30 percent of the market. There is nothing in the Constitution saying that business owners should be protected from more efficient competitors. And while size agnosticism might mean fewer small businesses, it certainly wouldn’t mean fewer jobs. If large or mid-sized companies took some market share from small businesses, not only would they employ more people, but by definition it would mean that products and services are cheaper which means consumers would spend their savings at other companies, creating jobs. And because productivity and innovation would be higher, consumers and workers would be better off.

So let’s level the size playing field.

Editors’ Recommendations

June 22, 2012

In Praise of Big Business: Part 1

June 1, 2015