Why the US Economy Needs More Consolidation, Not Less

Larger firms are generally more productive because of scale economies, but some U.S. industries still have too high a share of small firms. Policymakers should encourage, not discourage, greater consolidation in these industries.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Takeaways

Contents

Economies of Scale and Productivity 4

The Role of Consolidation in Improving Efficiency 5

Examining 12 Industries in 5 Sectors 7

Introduction

Larger firms are the key to productivity growth, as, in most industries, large firms are more productive than their smaller counterparts partly because of what economists term “economies of scale.” In some industries, there seem to be few scale effects. For example, it’s hard to imagine why a motor vehicle towing company with 5,000 workers would be more efficient than one with only 5. And many industries already have achieved close to optimal scale—although, of course, technology is constantly changing, which is one reason why companies may want to merge or divest. Yet, there are certain industries that appear to be able to benefit from scale economies but have not adequately done so, in part because government policy either restricts consolidation or rewards fragmentation.

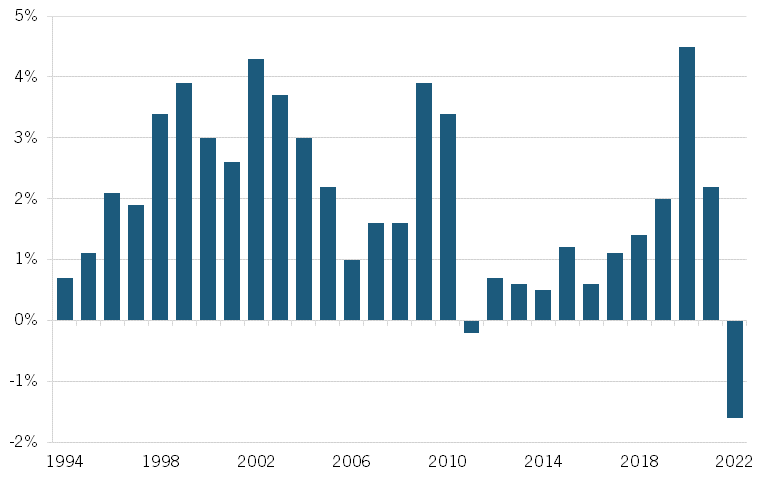

Although most policies are well-intentioned, many have an unintended negative impact on firm growth and consolidation. For example, while building codes protect us from faulty infrastructure, the lack of standardization across localities and states means that firms are discouraged from expanding to new areas, as they would have to learn a new set of codes, which would increase their costs. As a result, firms in many industries face barriers to reaching scale economies and greater efficiency. This is concerning because the United States’ nonfarm business labor productivity growth rate has been below average since 2005, leading to slower economic growth, stagnant wages, and reduced competitiveness. (2020 was an anomaly based on COVID reductions in employment in low productivity industries.) (See figure 1.) Increased consolidation, leading to greater scale economies, could play a role in reversing this trend.

Figure 1: Year-over-year growth in U.S. labor productivity[1]

Yet, consolidation is demonized by neo-Brandeisians and other proponents of the “small is beautiful” antitrust school, making it much harder to justify modifying policies that limit consolidation. Indeed, they have all but shunned the very idea that consolidation can be beneficial and, accordingly, the economic consensus that some firms can benefit from greater scale—all in order to support their claim that a small businesses-dominated economy is the ideal one. As Robert Atkinson and Michael Lind have asserted:

Neo-Brandeisians go out of their way to deny the very existence of scale economies because they know that this reality, more than any other, undercuts their claim that breaking up big companies would be good for the economy. Matt Stoller [at the American Economic Liberties Project and Open Markets Institute], reflects that view when he tweets, “I’m increasingly convinced the biggest con in business history is the notion of ‘economies of scale.’”[2]

Troublingly, the Biden administration has subscribed to the view that small firms are the ideal outcome for most industries. In addition to appointing neo-Brandeisians and their allies to top positions at the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and Department of Justice (DOJ), the administration stated in its Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy that “the problem of consolidation now spans these sectors and many others”—essentially demonizing greater consolidation without considering the benefits it could bring to at least some industries.[3] Yet, as the broad economic consensus shows, many industries do benefit from greater scale and consolidation.[4] Thus, policymakers subscribing to the “small is beautiful” doctrine need to reconsider how they view industry consolidation.

Policymakers thus need to promote greater consolidation in industries that benefit from large scale economies and that have not yet achieved such scale. The best way to do that is to modify or, if possible, remove government regulations—at the local, state, and federal levels—that disincentivize consolidation or promote fragmentation. This is necessary because doing so would allow efficient firms to stay in the market and grow while encouraging the less efficient ones to either merge or exit the market, boosting an industry’s productivity. As a starting point, the Biden administration should follow up on its prior executive order on competition with a new one, such as an “Executive Order on Removing Barriers to Consolidation in the American Economy” that would do at least two things. First, such an order would call for regulatory size neutrality to minimize bias toward firms of a specific size. Second, it would examine industries and policies with the goal of eliminating policies and regulations that keep industries too fragmented.

This report shows 1) that larger firms in the economy are generally more efficient due to scale economies, 2) how consolidation can help smaller firms maximize economies of scale, and 3) how 12 industries in 5 sectors (banking, doctor’s offices, construction, farming, and telecommunications) face barriers to consolidation because of government regulations. For each of the five sectors, it suggests what governments can do to enable market-based consolidation.

Economies of Scale and Productivity

The vast majority of industries in the economy enjoy scale economies for two reasons. The first is that most industries have not insignificant fixed costs that do not grow as output increases (a fact that is particularly true in the high technology markets that drive innovation). Firms producing a small output volume will face higher average costs because there are fewer units of output to spread out fixed costs. However, as output increases, the average cost of a unit of output goes down because fixed costs remain stable despite costs growing with revenues. For instance, it can be cheaper per unit of output to produce 100,000 items than 100 because specialized machines can be introduced. Second, every additional unit of production usually declines in cost as workers gain experience. These cost declines continue until the firm reaches an efficient scale wherein greater efficiencies are outweighed by rising inefficiencies from size (such as greater coordination costs).[5] The efficient scale varies by industry for a number of reasons, so it is difficult for governments to determine the “proper’ limit.

However, larger firms are generally more efficient than smaller ones in the vast majority of industries throughout the economy. In an analysis of large firms with over 500 employees from 938 six-digit NAICS industries, we found that the receipts per worker are higher than the industry average for 710 industries.[6] In comparison, the remaining 228 industries have receipts per worker that are less than the industry average, although some of this could be a result of their charging lower prices.[7] These 228 industries with lower receipts per worker than the average tend to be industries wherein massive scale is unnecessary to achieve the lowest costs. For example, large nail salons (NAICS: 812113) have receipts per worker of $40,854 compared with the industry average of $64,131.[8] Nail salons have few fixed costs and little returns from scale, meaning that their average costs will only decline by a minuscule amount after serving a number of customers. In fact, the marginal cost of serving an additional customer may increase if a nail salon becomes too large for idiosyncratic reasons, such as nail technicians getting in the way of one another. In other words, some industries are efficient with small firms partly because they do not need large outputs with many workers in order to maximize scale economies.

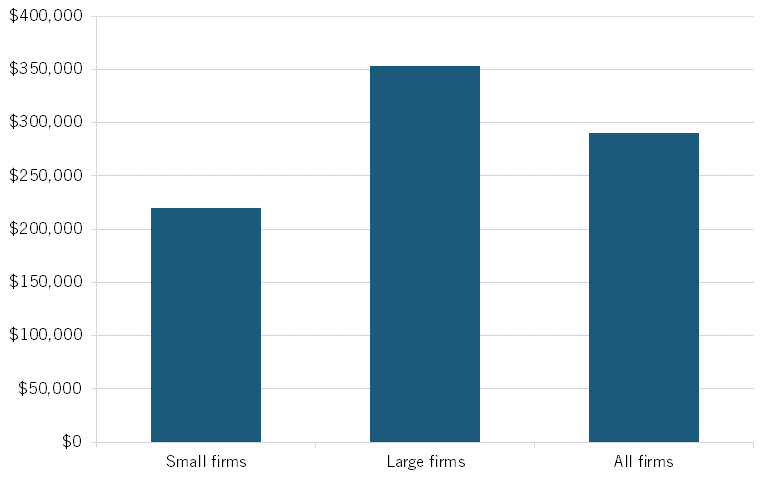

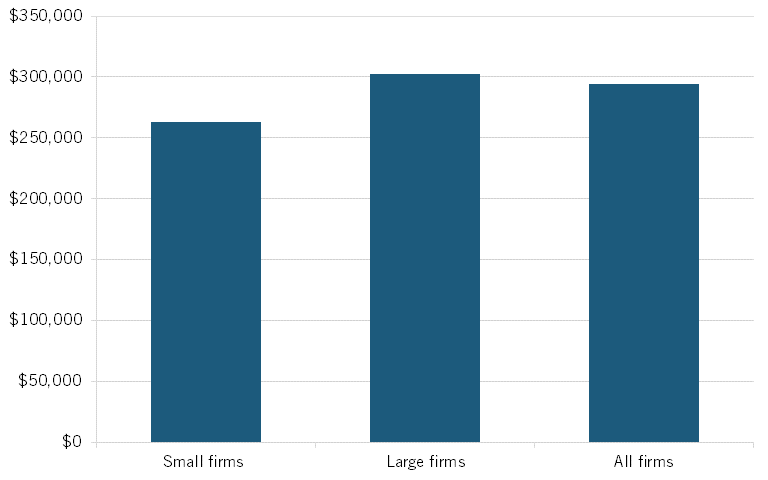

But most industries likely need large outputs to maximize scale economies. In 2017, the receipt of large firms in the average industry was 21.7 percent higher than the average firm in the economy, or $353,619, compared with the average firm’s $290,617.[9] Small firms’ receipts per worker were 24 percent lower than that of the average firm.[10] (See figure 2.)

Figure 2: Average receipts per employee across 938 six-digit NAICS industries[11]

The Role of Consolidation in Improving Efficiency

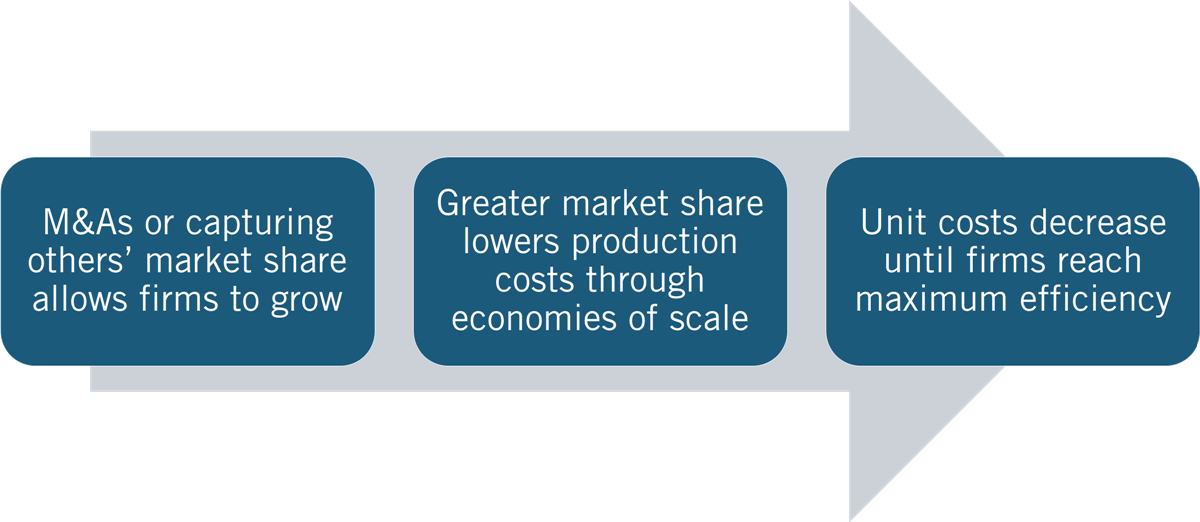

Consolidation is key to firms in industries with a high minimum efficient scale as a way to maximize efficiency. The process is as follows:

▪ First, consolidation in the form of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) or an increase in market share from one firm to another allows firms to become larger.

▪ As a result of their growth in size, these firms acquire a larger share of the market and can benefit from greater economies of scale to lower marginal production costs (or increased economies of scope or the elimination of double marginalization in conglomerate or vertical transactions).[12]

▪ Finally, as these firms continue to grow, they will eventually reach a point where their unit costs to produce an additional unit of goods can no longer decrease.[13] At that point, the firm has maxed out any efficiency gains from increasing scale.

In sum, consolidation helps firms maximize their efficiency from scale economies by becoming larger. (See figure 3.)

Figure 3: The process of increasing efficiency through consolidation

When consolidation increases a firm’s efficiency by achieving significant scale, it ceteris paribus increases the industry’s efficiency in partial equilibrium. This is why M&A is generally beneficial to firms and industries. When firms merge or acquire another firm, they can leverage scale economies and reduce costs through synergies, such as by combining their core knowledge.[14] For example, two stores need separate accounting, advertising, and purchasing services, but if these two stores combine, they can use a single set of services and workers to serve two customers, thereby reducing the overall costs of selling a unit of goods. Moreover, if these two stores have special processes that make their individual processes efficient, they can also share this know-how, further increasing the merged store’s efficiency. As a result, a merger creates incentives to reduce costs for firms and, additionally, improve the quality of a firm’s service or goods.[15]

There is an added reason to focus on this issue and that is the role of information and communications technology (ICT). Research has shown that adoption of ICT is a key driver of firm productivity. However, as a recent study by the U.S. Census Bureau shows, ICT adoption is positively correlated with firm size.[16] For example, 10 times more large firms adopted artificial intelligence (AI) than did small firms in 2020. One reason for this is there are often somewhat high fixed costs relative to marginal costs for information technology (IT) and software, and therefore the economics of adoption work better for larger firms.

As firm efficiency increases from greater M&A, an industry’s productivity will ceteris paribus also rise. This is because M&A redistributes resources between firms so that the more efficient, acquiring firm will be able to reduce costs, charge lower prices, and create competitive pressures in the market that drive out less-efficient firms. Indeed, a study by Joel David finds that M&A increases output by about 14 percent, and 9 of those percent result from improved productivity distribution of firms.[17] Demirer and Karaduman corroborated this with a study on power plants, which concludes that “high productivity firms buy underperforming assets from low-productivity firms and make the acquired assets almost as productive as their existing assets after acquisition.”[18] In other words, M&A, or consolidation, increases efficiency at the firm level and, ultimately, at the industry level.

Examining 12 Industries in 5 Sectors

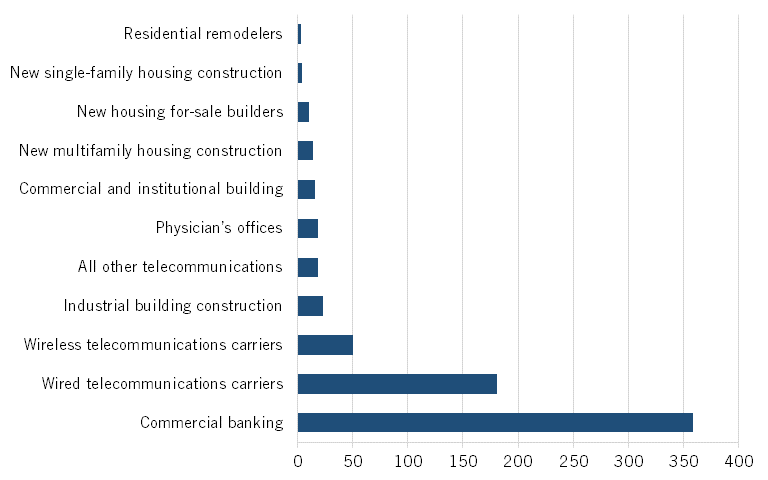

In the following five sectors—banking, doctor’s offices, construction, farming, and telecommunications—large firms are more productive because of scale economies, despite the fact that government regulations have kept or are keeping the industries in these sectors fragmented. This is why the average firm size for the 11 industries in these sectors is below 500 employees, or what the Small Business Administration describes as a “small business.”[19] (See figure 4.) The average farm size, measured using gross cash farm income (GCFI), was $207,756, or what the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) would consider a small farm.[20]

Figure 4: Average number of employees in studied sectors[21]

As a result of the small average firm size, we explore these five sectors as case studies in the following subsections. Each of the five subsections will provide evidence that 1) an industry benefits from scale economies, 2) larger firms are more productive, 3) government regulations disincentivize consolidation, and as a result, 4) how the industry still has a high share of small firms.

Banks

Larger banks are generally more efficient than small ones because of scale economies. Studies have found that the larger a bank grows, the greater its efficiency gains from scale economies. Indeed, studies by McAllister and McManus, Ferrier and Lovell, and Hunter and Timme have found that banks with over $1 billion in assets could still benefit from scale economies.[22] Further corroborating this finding, banks with over $1 trillion in assets were found to still have increasing returns to scale, meaning that they could still grow larger and benefit from scale economies.[23] In contrast, small banks with less than $100 million in assets are found to have substantial scale inefficiencies.[24] In other words, banks benefit from large scale economies.

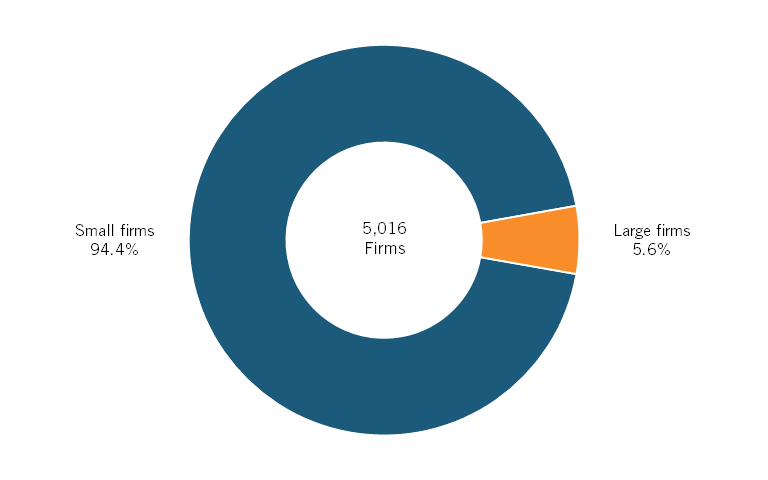

This helps explain data for 2017 showing that the average large commercial bank with more than 500 employees had a receipt per employee of $302,358, which was 2.6 percent higher than the industry average of $294,594.[25] In comparison, small commercial banks with less than 500 employees had a receipt per employee of $263,435, which was 10.6 percent lower than the industry average.[26] (See figure 5.)

Figure 5: Commercial banking receipts per employee[27]

Despite large banks’ greater productivity, government regulations have historically kept banks small by preventing consolidation. As early as the 19th century, states and the federal government already had a series of unit banking laws that prevented branch banking in order to protect small, local banks from competition and consolidation. At the state level, some states permitted their banks to operate branches within their headquartered state or within the same cities.[28] Yet, other states were much more restrictive and forced their banks to operate out of a single building.[29] At the national level, banks could only operate within a single building from 1863 to 1927.[30] As a result, these unit banking laws kept banks relatively small since they could only grow to a limited size and reach a limited share of the market, given the restriction on their location.

Although the McFadden Act of 1927 promoted the growth of national banks, allowing them to operate branches as long as they complied with state laws, the banking industry was still fragmented because, at best, each bank’s growth was still limited to the size of its state. Indeed, Robert Atkinson and Michael Lind asserted that these protectionist policies for small banks resulted in an industry with “thousands of tiny, undercapitalized ‘unit’ banks owned by members of the local gentry” while other nations’ industry comprised “a financial system dominated by a few national banks.”[31] As a result, while other nations’ branch banking policies eliminated bank runs in the early 20th century, the United States continued to face bank panics exacerbated by unit banking laws until the late 20th century, when the interstate banking laws were passed.[32] Moreover, the act also raised wages in the financial industry.[33] In other words, government regulations have historically undermined growth and consolidation in banking that could have led to scale economies benefits, fewer bank panics, and higher wages.

Yet, despite the consequences of historic unit banking laws, policymakers still insist on keeping banks small through regulation that discourages consolidation. In July 2021, the Biden administration signaled in its Executive Order on Promoting Competition that the administration plans on increasing scrutiny of bank mergers, writing, “To ensure Americans have choices among financial institutions and to guard against excessive market power, the Attorney General, is encouraged … to adopt a plan … for the revitalization of merger oversight under the Bak Merger Act.”[34] In response to the order, DOJ has “recently indicated it would take a more granular, wide-ranging approach to bank merger reviews amid increased antitrust scrutiny.”[35]

Rallying behind these detrimental policies, neo-Brandeisian antitrust critics have warned, “The total number of banks in America has fallen by some 60 percent since 1981, even as the population has grown substantially,” implying that large banks are gaining more monopoly power.[36] Truth be told, however, C4 and C8 concentration ratios—the four or eight firms with the highest market share—for commercial banks are declining: From 2002 to 2012, the C4 and C8 concentration ratios for commercial banks fell from 29.5 to 25.6 and from 41.0 to 35.8, respectively.[37] To be sure, it is one thing for one of the top-four banks in the United States to acquire another bank, which may or may not have competitive implications. But having 500 small and regional banks get bought up by larger banks is unlikely to reduce competition.[38]

Unfortunately, government regulations continue to impede the process of consolidation that encourages banks to maximize economies of scale. Indeed, these government regulations are partly why the industry still has a large share of small firms despite larger firms’ greater efficiency. In 2017, only 5.6 percent of commercial banks (281) were large, while the remaining 94.4 percent (4,735) were small.[39] (See figure 6.)

Figure 6: Small and large firms’ shares of the commercial banking industry[40]

With so many small banks, the United States has more banks per capita than most other nations. As Robert Atkinson and Michael Lind wrote:

But because most other nations never had American-style unit banking laws, they have always had significantly fewer banks per capita. In 1998 Japan had just 170 banks, or one bank for every 747,000 people. Canada, widely viewed as having the safest banking system in the world, had one bank for every 1.16 million residents. The United States has one bank for every 58,000 people. And in 1999, the share of deposits and assets of the five largest US banks was just 27 percent, compared to 77 percent in Canada, 70 percent in France and 57.8 percent in Switzerland.[41]

To encourage greater efficiency, the Biden administration should modify its executive order to encourage more bank acquisitions rather than discourage them. In the modified executive order, the administration should encourage the FTC and the DOJ Antitrust Division to review mergers between small and regional banks—not including mergers by the largest four or five largest banks nationally—with a focus on how efficiency gains can potentially outweigh the increases in concentration. Doing so would allow the banking industry in the United States to benefit from increasing returns to scale. As Robert Atkinson and Michael Lind asserted:

But even with the number of banks falling by more than half in the last few decades bank economies of scale have still not been exhausted and the United States still suffers from too many banks. As the Federal Reserve has found, even the largest banks face increasing returns to scale … The Fed found, ‘Our results suggest that capping banks’ size would incur opportunity costs in terms of foregone advantages from IRS’ … Other studies have found similar results.[42]

In other words, when the administration encourages greater bank consolidation, it will also encourage greater bank efficiency because banks will become larger and benefit from increasing returns to scale.

Physician’s Offices

Larger doctor’s offices are generally more efficient than small ones because of scale economies. To best serve their patients, doctor’s offices must adopt new technologies and medical treatments. However, the cost of implementing these new methods is often high, meaning doctor’s offices face high fixed costs to obtain the tools needed to treat patients. As a result, a larger doctor’s office can serve more patients to spread out its fixed costs and lower its average cost.[43] Indeed, case studies of 14 small primary care practices find that only some of these practices could cover the $44,000-per-doctor cost of electronic health record software after 2.5 years, suggesting that small doctor’s offices do not have the scale to implement even the most basic efficiency-enhancing technologies.[44] This is why Baker, Bundorf, and Royalty concluded that multispecialty group practices are more likely than single specialty groups (which tend to be smaller) to benefit from scale economies.[45] For example, One Medical, a large national practice group recently purchased by Amazon, has its own in-office laboratories for blood work and related analysis.

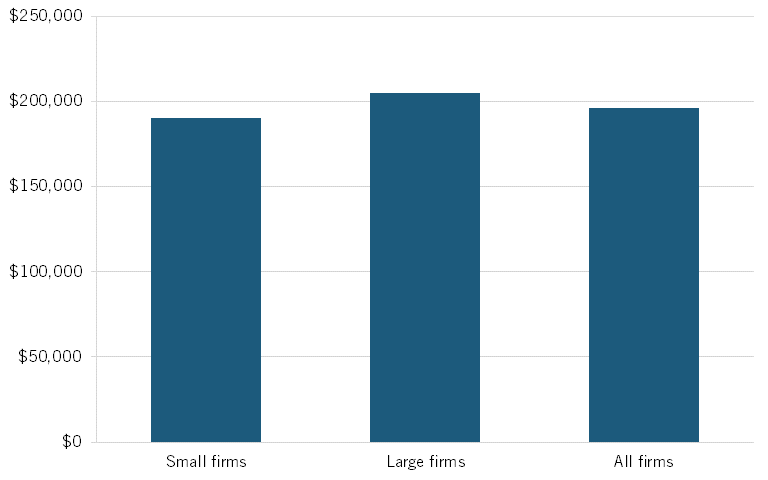

The data is in accord. In 2017, large physician’s offices had a receipt per worker of $204,931 compared with average small firms’ receipts per employee of $190,182.[46] In other words, large firms were 4.6 percent more productive than the average while small firms were 3 percent less productive. (See Figure 7.)

Figure 7: Receipts per employee in physician’s offices (not including mental health specialists)[47]

Despite the benefits that doctor’s offices can gain from scale, government regulations at the federal and state level have historically been an impediment to the growth of doctor’s offices. For example, in 1964, New York adopted the Certificate of Need (CON) law, restricting the construction of new hospitals under the assumption that the restriction of capital expenditures could reduce the high cost of health care.[48] As the American Hospital Association lobbied for more states to also adopt similar regulations, the federal government passed a mandate in 1974 to have all states implement a CON program as part of the National Health Planning and Resources Development Act.[49] As a result, all states, except Louisiana, had a CON law by 1980.[50] This meant that hospitals and any other health care facilities included in these regulations faced the burden of having to apply for, and then the possibility of being denied, whenever they considered expanding their facilities. In other words, these CON laws prevented growth and consolidation by raising the cost of growth, thereby limiting doctor’s offices’ efficiency gains from scale.

Although the federal government repealed its mandate in 1986 because the law didn’t lower health care costs, 35 states still had CON laws as of 2020.[51] These laws continue to prevent growth and consolidation in the physician’s offices industry, reducing their benefits from scale economies. Indeed, Maureen Ohlhausen, former commissioner of the FTC, wrote that “CON laws actively restrict new entry and expansion. They displace free market competition with regulation and tend to help incumbent firms amass or defend dominant market positions.”[52] In other words, these regulations protect small incumbent firms that are unwilling to grow and compete fairly while simultaneously disincentivizing others from consolidating and becoming more efficient from scale economies and embracing more patient-friendly information technology systems.

In addition to the CON laws, state governments have continued to impose other regulations that stifle consolidation in the industry. In the last year, states have passed laws that increased the burden for merging parties in the healthcare industry. For example, New York recently passed a law that requires health care entities to give a 30-day notice before closing a deal, while Maine repealed a law that exempted certain health providers’ mergers from antitrust laws.[53] Additionally, consolidation in the industry could also slow in California next year when all M&A deals have to be reviewed and approved by the Office of Health Care Affordability.[54] Indeed, the National Academy for State Health Policy has advocated for more of these legislations with its Model Act for State Oversight of Proposed Health Care Mergers, which calls for greater scrutiny of health care mergers through state regulation.[55] As such, consolidation in the industry is already slow and will likely continue to be slow in the future, hurting firms’ ability to achieve scale and greater efficiency.

Despite the benefits that doctor’s offices can gain from scale, government regulations at the federal and state level have historically been an impediment to the growth of doctor’s offices.

Indeed, CON laws and other regulations that stifle consolidation still exist because proponents of the antimonopolist tradition continue to assert that policymakers should protect small firms from competition—when they should really be encouraging them to grow and compete—despite reduced efficiency. As a result, consolidation in the doctor’s offices and physician groups industry more generally is demonized even if it can bring efficiency gains. For example, a New York Times article asserts that “the absorption of doctor’s practices is part of a vast, accelerating consolidation of medical care, leaving patients in the hands of a shrinking number of giant companies or hospital groups.”[56] Meanwhile, Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) asserted that she has a fear “that the acquisition of thousands of independent providers by a few massive health care mega-conglomerates could reduce competition on a local or national basis, hurting patients and increasing health care costs.”[57]

This combination of state regulations and paranoia among policymakers is partly why the industry still has a large share of small firms despite the higher productivity of large firms. In 2017, large firms comprised only 0.6 percent of physician’s offices (not including mental health specialists). There were 919 such offices. The remaining 99.4 percent of physician’s offices were small (160,367 offices).[58] (See figure 8.)

Figure 8: Small and large firms’ shares of physician’s offices (not including mental health specialists)[59]

![]()

To encourage greater efficiency, state governments should take two steps to encourage greater consolidation in the doctor’s offices industry. First, they should repeal CON laws if their state still has one in existence. This would encourage doctor’s offices to consolidate and grow larger without higher costs or fear of repercussions from this law that specifically prohibits firm expansion without extensive review. Second, the state governments should conduct a broad review of their state regulations and compile a list of all regulations relevant to physician groups in order to find those that create a barrier to consolidation and firm growth, and then modify those regulations so that they continue to serve their purpose without impeding consolidation. In addition, some regulations that have the sole purpose of impeding consolidation, such as those pertaining to M&A approvals, should be modified to focus on balancing efficiency gains with competitive effects.

Construction

Larger construction firms are also generally more efficient because of scale economies. Construction projects are often complex, face uncertainty, and require high levels of coordination between multiple actors, such as architects, designers, manufacturers, and other contractors.[60] As a result, the most efficient construction firms have to adopt technologies that increase collaboration and coordination in the project value chain.[61] For instance, Swissroc, a Swiss construction firm, adopted a single centralized platform for its workflows that resulted in higher-quality buildings, more referrals, and a 300 percent increase in revenue. Yet, adopting these technologies means high fixed costs for firms.[62] As a result, larger construction firms are better positioned to manage risk and adopt new technologies to funnel the projects along at greater efficiency because they can spread out the costs among more projects. Accordingly, there are strong incentives for M&A in construction, including their post-merger sales being higher than their combined sales as individual firms.[63]

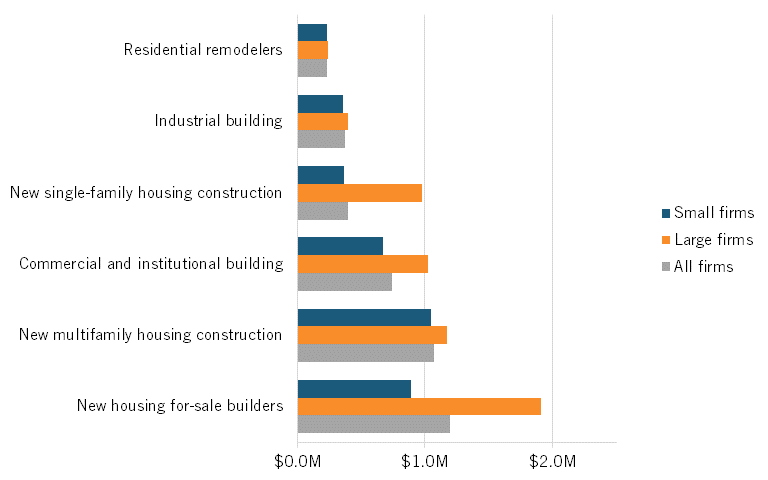

Indeed, the data supports this. In 2017, large construction firms with over 500 employees were 4 to 148 percent more productive than the industry average.[64] Small construction firms were 2 to 25 percent less productive than their respective industry’s average.[65] For instance, the large firms in the commercial and institutional building construction industry were 38 percent more productive than the industry average, with its receipts per employee at $1.03 million compared with the industry average of $744,462.[66] Yet, the small firms in this industry were 10 percent less productive than the industry average, with a receipt per employee of $672,831.[67] (See figure 9.)

Figure 9: Construction receipts per employee[68]

Despite the greater efficiency of larger firms, the construction industry has historically been and continues to be extremely fragmented because of the extensive unstandardized local and state regulations that have been imposed. Indeed, as early as the 1800s, U.S. cities began establishing regulations that would affect how the construction industry would operate. For example, the California Real Estate Inspection Association notes that larger U.S. cities implemented building codes as early as the 1800s, with New Orleans establishing a law in 1865 that required public property inspections.[69] By the 1880s, a myriad of local jurisdictions had also implemented their own versions of exit requirements, plumbing regulations, and hoist and elevator regulations.[70] As such, the idiosyncratic nature of these early regulations likely discouraged early construction firms from growing into other jurisdictions, disincentivizing growth and consolidation.

By the 1980s, these unstandardized regulations affected every aspect of the construction industry. State and local jurisdictions had implemented such an extensive range of regulations that construction firms had to navigate regulations on aesthetics, demolition, environmental protection, explosives, liability, material and equipment acceptance, and wages, among others.[71] This meant that construction firms that wished to expand now faced high entry barriers because they had to 1) familiarize themselves with a wide range of regulations that impacted the industry and 2) navigate the differences between these regulations from one jurisdiction to another. As such, construction firms faced higher costs when operating in more than one jurisdiction, disincentivizing them from consolidating and growing. Indeed, this is why construction industry expert Barry LePatner wrote in his book that “everyone associated with the process of purchasing land and building on it over the last twenty-five years know that regulation has grown exponentially … there is little double that the current system of government regulation … is repressive enough to impede U.S. productivity growth.”[72]

These unstandardized regulations still place burdens on construction firms seeking to expand. For example, at the local level, construction firms have to abide by local building codes, which vary greatly by local jurisdiction. These include permits, approvals, safety and worksite controls, and public sector mandates for lowest price rules, among other regulations.[73] As a result of these unstandardized local regulations, construction firms are hesitant to consolidate or grow—even only slightly to the next local jurisdiction—because they face higher risks working in a jurisdiction where they are unfamiliar with the regulations. In fact, even a uniform building code can have different interpretations depending on the area. For example, Richard Mettler of the Home Builder Association of Phoenix asserted that the one local building code governing the greater Pheonix area isn’t even uniform because the officials in Pheonix have a different interpretation of the code than do those in Tempe or Mesa.[74]

Despite the greater efficiency of larger firms, the construction industry has historically been and continues to be extremely fragmented because of the extensive unstandardized local and state regulations that have been imposed.

Assuming that a construction firm wants to expand across state lines, unstandardized state regulations become the next barrier they have to overcome. For example, mechanics’ lien laws— a legal tool that enables contractors, subcontractors, and suppliers to recover compensation for unpaid construction work or for materials they have supplied—vary by states. For instance, the mechanics’ lien law in Alaska asks for construction firms to prove that an owner consented to a firm’s services; yet, other states do not mention who has the burden of proof in the regulation.[75] These variations mean that construction firms will have to familiarize themselves with the lien law for each state they operate in or hire a professional to help. In other words, they will either have to face the opportunity cost of time to understand each new regulation or the cost of hiring a professional. In either case, the cost of operating in multiple states increases the cost for construction firms, disincentivizing them from consolidating or growing.

As such, local and state governments should work to standardize the regulations imposed on the construction industry to encourage consolidation. These recommendations are not new. MIT professor Kelly Burnham called for “national acceptance of a standard building code for plumbing” as early as 1959.[76] Others have suggested that the standardization of building codes would reduce costs. Yet, despite these calls and evidence that greater consolidation can benefit the industry, regulations are still highly fragmented across local and state jurisdictions. This is partly why a participant at an Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) event asserted that the construction industry is “America’s sole remaining ‘mom and pop’ industry [that] wastes at least $120 billion each year” due to its inefficiencies.[77]

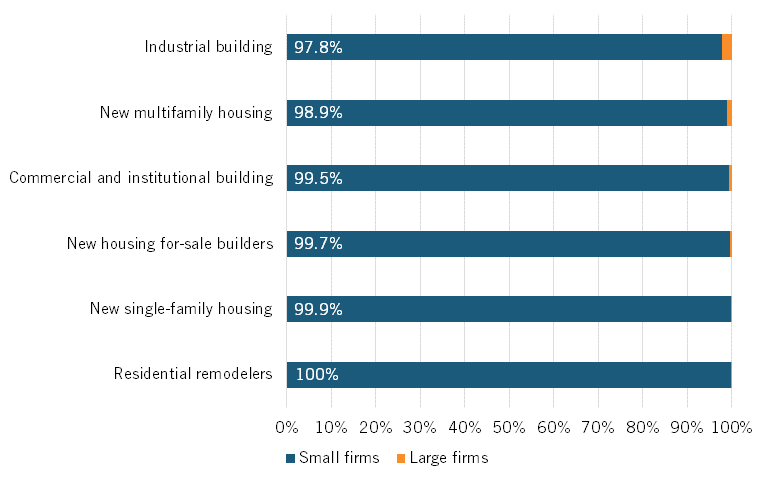

This is supported by the data. The construction industry has a large share of smaller, less-efficient firms. In 2017, the six construction industries under the 2-digit NAICS construction sector had between 0.1 and 2.2 percent of large firms in their industry, meaning that a vast majority of firms were still small and had not reached scale economies.[78] For example, the new single-family housing construction industry had 49,215 firms, but only 34 had more than 500 employees. (See figure 10.)

Figure 10: Small firms’ share of construction industries[79]

First, to encourage greater efficiency, the federal government could publish a standardized set guidelines on 1) the type of regulations the industry should have and 2) how to set regulations for the construction industry so that it encourages greater consolidation. Although the federal government cannot limit state regulations, it can encourage greater cohesiveness in regulations across states so that construction firms face fewer barriers when consolidating and expanding across state lines. Furthermore, setting guidelines on how to set regulations so that it encourages consolidation can also be an indirect way to prevent future state regulations from impeding firm growth.

Second, state governments can also encourage greater consolidation by implementing a standard set of regulations for the industry that effectively preempt local regulations. This will ensure that firms face fewer costs and barriers when expanding across local jurisdictions because they will only have to understand a standardized state regulation rather than multiple varying sets from each local jurisdiction. With fewer barriers, firms will be encouraged to consolidate and grow, increasing their efficiency.

Farming

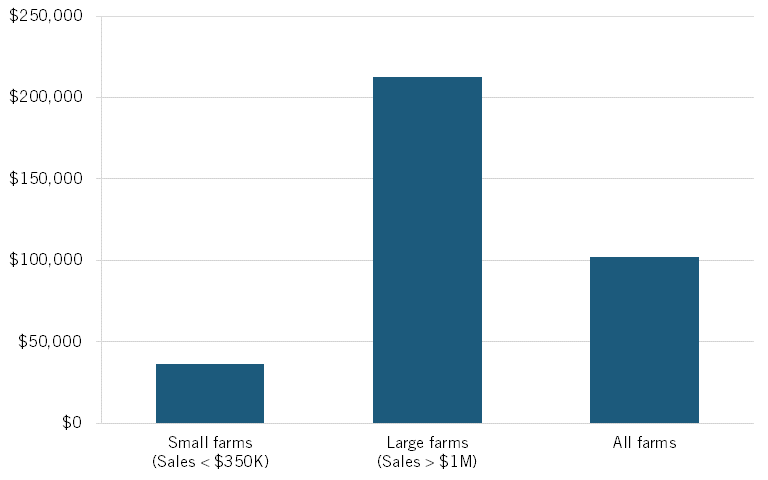

Notwithstanding the sentimental views toward small, family farms, larger farms are generally more efficient than their smaller counterparts partly because of scale economies. According to Purdue University, 53 percent of costs (land, machinery, and labor) in agricultural production are fixed.[80] As a result, large farms producing more yields benefit from increasing returns to scale as a higher output reduces the average cost of production. In fact, a study of the heartland and Northern Crescent states finds that scale economies are the driving factor for farm efficiency and competitiveness in the economy.[81] Simply put, larger farms are generally more efficient. Accordingly, a study by MacDonald, Hoppe, and Newton concludes that a full-time employee at a large farm generates annual sales of $212,766 compared with $36,630 for a small farm producing less output.[82] This is compared with the average farm’s annual sales of $102,145 per full-time employee.[83] (See figure 11.)

Figure 11: Farm receipts per full-time employee[84]

Despite the greater efficiency of larger farms, government intervention in the form of farm subsidies has historically disincentivized consolidation in the industry. The original intent of these subsidies was to help cash-strapped farmers during the Great Depression. During the height of the Great Depression, President Roosevelt passed the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) as part of the New Deal to curtail the output of crops and livestock in order to stabilize farmers’ income amid the production of excess crops and low prices.[85] Yet, these interventions continued after the Great Depression even though they could no longer be economically justified.

According to the Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank, the AAA was not repealed after the Great Depression but instead became a permanent price adjuster for six basic commodities so that their levels were “relative to the general prices levels in the 1910-1914 period” even during periods when farm incomes were strong.[86] In addition to the AAA, the government continued adding other farming subsidies—such as supply controls—that fixed prices for farmers over the next few decades. As a result, farmers no longer had to worry about competing or becoming more efficient in the economy because the government subsidies would essentially guarantee price and revenue to farmers with no strings attached. Indeed, the Private Enterprise Research Center at Texas A&M University concluded that farm subsidies are inefficient because they incentivize farmers to make decisions that will get them the most subsidies rather than “fetch the best price on the open market.”[87] In other words, government subsidies disincentivized farms from consolidating, reaching scale economies, and growing more efficient than they were during this period.

Today, government subsidy programs continue to disincentivize farms from consolidating and becoming more efficient. Indeed, the U.S. Department of Agriculture spends about $30 billion a year on farm subsidies, which include crop insurance programs, agricultural risk coverages, price-loss coverages, and ad hoc and disaster aid relief, among others.[88] Although some support programs are reasonable, such as the conservation program, numerous other programs are just a form of government intervention that impedes the process of competition while disincentivizing growth and efficiency when resources are handed out without any strings attached. For example, the crop insurance program is a farm subsidy program that covers over 100 crops, paying out billions of dollars a year to farmers when their crop yields or revenue is reduced.[89] Moreover, most farmers do not have to pay the insurance premium to enroll in this program: The government subsidizes nearly 62 percent of premiums.[90] As such, farms have little incentive to consolidate and adopt specialized equipment that will help manage risks and reduce costs because the government removes risks and guarantees revenue with its subsidies.

Despite the greater efficiency of larger farms, government intervention in the form of farm subsidies has historically disincentivized consolidation in the industry.

The crop insurance program is just one of many government subsidy programs that disincentivize farms from consolidating to increase efficiency. The Price Loss Coverage program and the Agricultural Risk Coverage program are two other programs that also guarantee price and revenue to farmers.[91] Both programs make payments to producers when market prices or revenues fall below a certain level.[92] Similar to the AAA and other subsidy programs in the 20th century, these two programs disincentivize growth and efficiency because farmers no longer have to compete based on who can offer the lowest price to consumers to gain revenue.[93] Instead, they just have to focus on how to obtain the most subsidy from the government.[94] As such, instead of finding ways to grow and become more efficient, farms are figuring out how to shift from growing wheat to corn because corn is more likely to fetch higher subsidies in a given year.

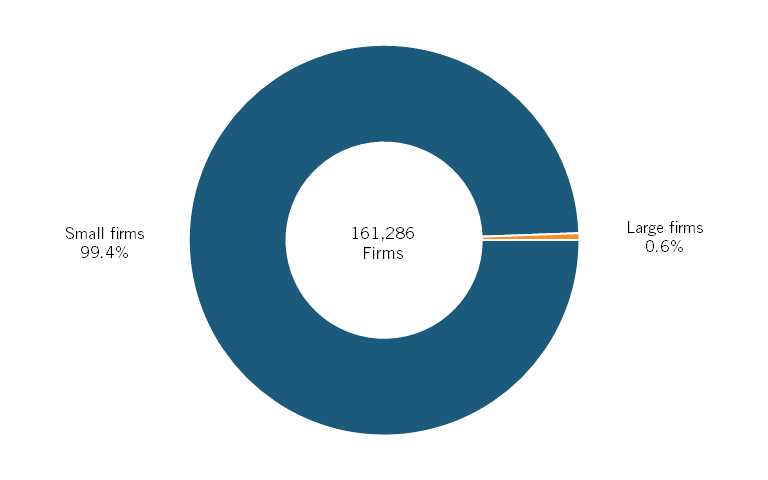

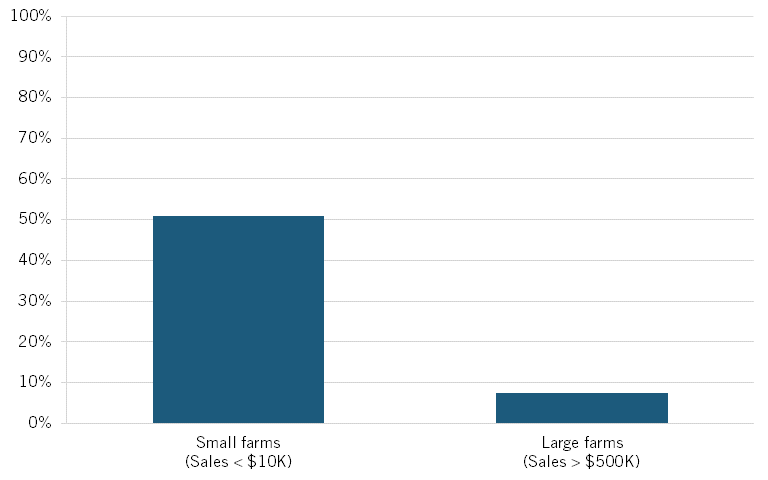

As a result, government subsidies are one of the reasons the industry still has so many smaller, less-efficient farms. In 2021, the U.S. Department of Agriculture found that 51 percent of all farms had sales less than $10,000 and only 7.4 percent had sales of over $500,000.[95] (See figure 12.)

Figure 12: Farming market shares[96]

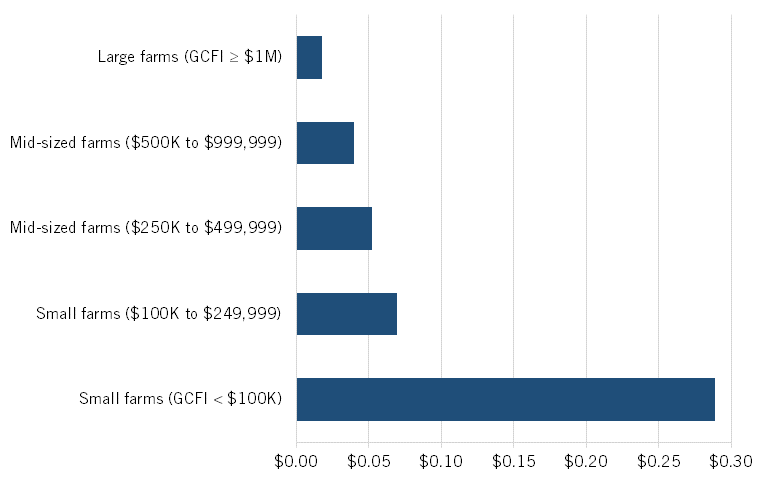

To be sure, many of these smaller farms depend on subsidies for income. A USDA technical paper finds that many small and medium-sized farms receive some program benefits from the government, with only one in four able to sell enough to cover their costs.[97] The government payments tend to be greater than sales for the smallest farms, and 90 percent of their sales and government payments are derived from government subsidies.[98] Indeed, controlling for size, small farms, defined by USDA as those with less than $100,000 in GCFI, received $0.29 per dollar of sales while large farms (more than $1 million in GCFI) only received $0.02 cents.[99] (See figure 13.) In other words, government subsidies disincentivize growth and consolidation because large farms generally get less than small farms when their size is controlled for.

Figure 13: Government subsidies per dollar of sales[100]

To encourage greater efficiency, the federal government should not eliminate subsidies for revenue because they ensure a stable food system. Instead, they should tie subsidies to farm efficiency gains or farms’ efforts to improve their efficiency. In other words, the government should first establish a productivity measure for farms and then establish a new set of policies that only provide subsidies to farms that have experienced productivity gains in the preceding five years (five years because it will likely take time for efforts to increase efficiency to show in productivity measures). Alternatively, the government can also tie subsidies to a farm’s efforts to increase its efficiency, such as by adopting specialized equipment. Moreover, the government should also establish regulations that prevent farms from manipulating the types of crops produced in order to receive higher subsidies. As a result of these policies, the government will encourage farms to consolidate as they search for ways to increase their efficiency without endangering the stability of the food system.

Telecommunications

Larger telecommunications firms are also generally more efficient than smaller ones because of scale economies. Telephone and Internet service providers (ISPs) pay extremely high up-front costs, face limited materials and labor forces, and see a return on investment tied directly to the number of customers in a particular area. The provision of telecom and broadband services is also highly complex, technical work that requires considerable investments in infrastructure and development.[101] Because a large number of potential customers is needed to recoup even the up-front costs of a project, small telecom providers are generally quite easily priced out of the market, or need heavy, ongoing government subsidies to survive. Large firms have easier access to the massive up-front funds needed, entrenched institutional knowledge that can help them avoid pricey mistakes, and widespread existing broadband networks and customer bases that are more cost-effectively expanded than built anew.

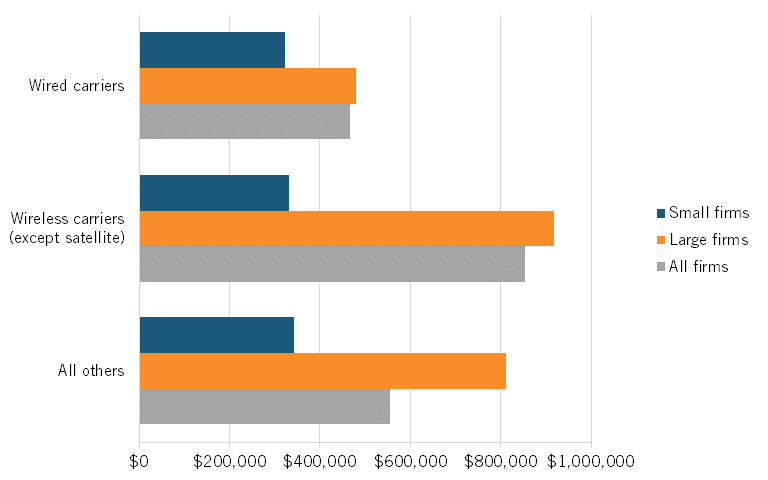

The data is in accord. For wired telecommunications carriers, wireless telecommunications carriers (except satellite), and all other telecommunications industries, large firms range from 3 to 46 percent more productive than their respective industry’s average. By contrast, small firms are 31 to 61 percent less productive than their respective industry’s average.[102] For example, the large firms in the wireless telecommunications carriers industry are 7 percent more productive than the industry average, with receipts per employee of $916,985 compared with the industry average of $854,583.[103] This is compared with the small firms’ receipts per employee of $331,056, or 61 percent less efficient than the industry average.[104] (See figure 14.)

Figure 14: Telecommunications industries’ receipts per employee

Despite the greater efficiency of larger telecom firms, government policies discourage consolidation in the telecommunications industry. This is because some government subsidy programs that enable telecom services in high-cost areas are biased toward smaller providers. For instance, the High Cost Loop support program under the High Cost Fund is biased toward smaller providers. Indeed, historically, the subsidy was based on a formula that only provided support to the telecom companies whose costs were a specified percentage above the national average. As a result, if two companies merge and achieve scale economies, they risk losing this subsidy because their cost to provide service may no longer exceed the national average by the designated percentage. Thus, this means that the telecom companies receiving this subsidy has every incentive to shun growth and consolidation that could result in lower costs and greater efficiency.

Although a vast proportion of telecom companies that once received this subsidy have moved over to the more cost-efficient Alternative Connect America Model (ACAM) of support, some companies are still receiving the High Cost Loop support. However, the continuation of High Cost Loop support as an option for telecom providers is concerning because the subsidy still uses the same formula that caused inefficiencies in the past. According to the Universal Service Administrative Co., the subsidy is still only available to rural companies whose costs to provide service exceeds 115 percent of the national average cost per line.[105] In other words, telecom companies face the risk of losing support if their costs suddenly fell below 115 percent of the national average. As a result, companies still receiving this subsidy have no incentive to consolidate, achieve scale economies, and reduce costs.

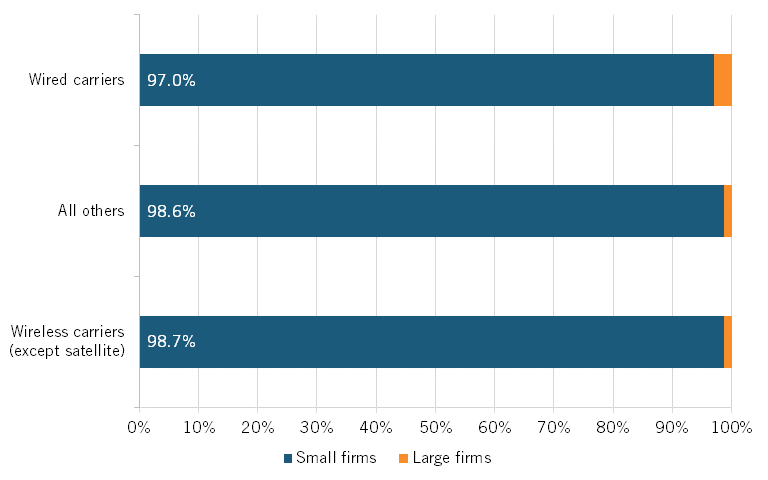

Indeed, the bias toward small firms in subsidies is partly why the three different telecom industries still have a large share of small firms. In 2017, these industries had 1.3 percent to 3 percent of large firms with more than 500 employees, meaning all three industries still have a vast majority of firms that have yet to maximize scale economies.[106] For example, the wired telecommunications industry has only 100 large firms but 3,264 small firms, meaning large firms only make up 3 percent of all firms.[107] This means that growth in size of the 3,264 small ones can lead to greater efficiency from scale economies. (See figure 15.)

Figure 15: Small firms’ share of telecommunications industries[108]

In sum, subsidy programs are undoubtedly necessary to close the digital divide, but the method of subsidy distribution needs to be revamped to encourage greater consolidation in the industry. The best way to do so is to eliminate the High Cost Loop support program and move the remaining telecom companies still receiving this subsidy to the ACAM of support. This is because the provision of subsidy through the ACAM model does not hinge on a firm’s cost, meaning that two telecom companies looking to merge for efficiency gain can do so without losing subsidies. As such, moving the remaining firms to the ACAM model could only result in efficiency gains as smaller telecom companies choose to consolidate in order to maximize their scale economies. In the case that the telecom companies still receiving the High Cost Loop support resist the move to the ACAM model, an alternative solution would be that the formula for the provision of High Cost Loop support is modified so that it is not based on whether a provider has high costs. Regardless of the solution pursued, the main goal is to ensure that firms seeking to consolidate and become more efficient can do so without losing subsidies.

Policy Recommendations

At the broadest level, policymakers should focus on developing policies and programs that encourage small firms to grow, merge based on scale economy benefits, and compete rather than rely solely on government assistance programs for survival.

Going beyond that, policymakers should be focused on ensuring that current government policies and programs do not disincentivize greater consolidation in industries characterized by high minimum efficient scale. For instance, the 12 industries in 5 sectors studied all benefit from scale economies, and that is why the large firms in these industries are generally more productive than their smaller counterparts. Yet, these industries still have many small firms, some of which are the result of market conditions, but others are from government policy distortion. Policymakers should encourage an increase in firm size for these and related sectors through greater consolidation from M&A or the loss of market shares from one firm to another. This means policymakers should modify or remove the local, state, or federal government regulations that discourage consolidation in these industries.

The Biden administration should draft a new executive order on competition that explicitly looks for instances when government policies keep firms in particular industries too small and unproductive. The goal of the order should be to eliminate regulations that keep these industries fragmented. The administration should also create an interagency body to examine whether an industry benefits from large scale economies and, if so, whether the regulations in that industry are discouraging consolidation. It would also have the task of recommending ways to modify or, if possible, remove existing regulations that discourage consolidation without harming those that the regulations are meant to protect (e.g., standardizing building codes rather than eliminating them).

The Biden administration should draft a new executive order on competition that explicitly looks for instances when government policies keep firms in particular industries too small and unproductive.

Finally, FTC and DOJ should not modify their merger guidelines and premerger notification rules. This is because their recent decision to change the merger guidelines, premerger notification rules, and Premerger Notification and Report Form will discourage consolidation for industries with high minimum efficient scale. First, the merger guidelines will discourage consolidation because they no longer acknowledge that mergers can increase efficiencies. This means mergers will face more scrutiny and denials even if their efficiencies balance out anticompetitive effects.[109] Second, the modifications to the premerger notification rules and form will increase the burden that firms face when filing merger notifications with the new, extended lists of documents that were not previously required.[110] These changes will decrease the value firms place on M&A, reducing their incentive to consolidate. As such, the amendments in these two federal regulations are also government distortions that need to be modified in order to promote greater consolidation and efficiency in industries wherein large firms are more efficient, but small firms are still too many.

Conclusion

In a majority of industries in the U.S. economy, larger firms are generally more productive than their smaller counterparts partly because of scale economies. One way firms within these industries can achieve this greater scale and efficiency is through consolidation. This is because consolidation, often through mergers between rivals, increases firms’ sizes through growth. As such, a growth in average firm size and efficiency can also increase an industry’s productivity. To be sure, antitrust policy is important to ensure that scale benefits are not outweighed by anticompetitive incentives to raise prices, reduce output, or diminish innovation. Yet, government regulations at the local, state, and federal levels in industries with large scale economies often unnecessarily discourage consolidation even when the industry still have a large share of small firms.

As such, policymakers need to ensure that policies—including antitrust, regulation, tax, and subsidies—at all levels of government are size neutral. Given that many regulations still disincentive growth and consolidation, the first step for policymakers is to modify or, if possible, remove these regulations in industries characterized by large scale economies. This is critical because the economy is made up of both large and small firms that need different levels of scale economies to thrive: The U.S. economy needs both dry cleaners and semiconductor fabrication plants, but expecting a semiconductor plant to have only five employees, much like a dry cleaner would, to produce millions of chips would be unreasonable—and it goes without saying that having 1,000 employees to dry clean clothes for a local neighborhood would be just as unreasonable.

Regulations should not disincentivize consolidation or growth, but rather incentivize firms to grow to as big or as small as they need in order to be efficient, including through M&A. In so doing, size-neutral regulations would help the U.S. economy because all firms would have incentives to grow to an efficient scale. As such, this could be the first step to reversing the United States’ declining productivity growth since 2005. Also, when firms maximize their efficiencies from scale economies, they are also in a better place when competing in the global market against foreign competitors. If policymakers want a productive, growing economy that can compete globally, they need to remove regulations that demonize consolidation and larger firms.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Robert Atkinson, Joseph Coniglio, Joe Kane, Lilla Kiss, and Jessica Dine for their feedback and assistance on this report. Any errors and omissions are the author’s alone.

About the Author

Trelysa Long is a policy analyst for antitrust policy with ITIF’s Schumpeter Project on Competition Policy. She was previously an economic policy intern with the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. She earned her bachelor’s degree in economics and political science from the University of California, Irvine.

About ITIF

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute that has been recognized repeatedly as the world’s leading think tank for science and technology policy. Its mission is to formulate, evaluate, and promote policy solutions that accelerate innovation and boost productivity to spur growth, opportunity, and progress. For more information, visit itif.org/about.

Endnotes

[1]. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Productivity and Cost Measures for Major Sectors (labor productivity change from previous year for nonfarm business sector), accessed November 2, 2023, https://www.bls.gov/productivity/tables/.

[2]. Robert D. Atkinson and Michael Lind, Big is Beautiful (Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2018).

[3]. “Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy,” The White House, July 9, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/07/09/executive-order-on-promoting-competition-in-the-american-economy/.

[4]. Maureen Ohlhausen and Taylor Owings, “Evidence of Efficiencies in Consummated Mergers,” U.S. Chamber of Commerce, June 1, 2023, https://www.uschamber.com/assets/documents/20230601-Merger-Efficiencies-White-Paper.pdf.

[5]. Lale Davut, “The Minimum Efficient Scale: A Note on Terminology,” https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/36306.

[6]. U.S. Census Bureau, Statistics of U.S. Businesses (U.S. & states, 6-digit NAICS), accessed November 9, 2023, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/econ/susb/2017-susb-annual.html.

[7]. Ibid.

[8]. Ibid.

[9]. Ibid.

[10]. Ibid.

[11]. Ibid.

[12]. T. R. Bishnoi and Sofia Devi, “Cost Efficiency and productivity,” in Banking Reforms in India, edited by Philip Molyneux (Bangor: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 121-163, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-55663-5_5.

[13]. Ibid.

[14]. Markus Berger-de Leon et al., “Buy and scale: how incumbents can use M&A to grow new businesses,” McKinsey and Digital, December 21, 2022, https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/buy-and-scale-how-incumbents-can-use-m-and-a-to-grow-new-businesses; https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8v1500b8.

[15]. Joseph Farrell and Carl Shapiro, “Scale Economies and Synergies in Horizontal Merger Analysis” (working paper, University of California, Berkeley Competition Policy Center, October 2000), https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8v1500b8; https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/704069.

[16]. Nikolas Zolas et al., “Advanced Technologies Adoption and Use by U.S. Firms: Evidence from the Annual Business Survey” (working paper at the Center for Economic Studies, December 2020), https://www2.census.gov/ces/wp/2020/CES-WP-20-40.pdf.

[17]. Joel David, “The Aggregate Implications of Mergers and Acquisitions,” The Review of Economic Studies 88, no. 4 (2012), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2033555.

[18]. Mert Demirer and Omer Karaduman, “Do Mergers and Acquisitions Improve Efficiency: Evidence from Power Plants” October 27, 2022, https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/demirerkaraduman.pdf.

[19]. Small Business Administration, “Frequently Asked Questions,” March 2023, https://advocacy.sba.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Frequently-Asked-Questions-About-Small-Business-March-2023-508c.pdf.

[20]. United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Resource management Survey (ARMS) (gross cash farm income for all farms), accessed January 20, 2023, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2021/econ/susb/2021-susb-annual.html.

[21]. U.S. Census Bureau, Statistics of U.S. Businesses 2021 (U.S. & states, 6-digit NAICS), accessed January 22, 2024, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2021/econ/susb/2021-susb-annual.html.

[22]. Robert DeYoung and Gary Whalen, “Banking Industry Consolidation: Efficiency issues” (working paper, Jerome Levy Economics Institute Working Paper No. 110, 1998), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=126288.

[23]. Loretta Mester, “Scale Economies in banking and Financial Regulatory Reform,” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, September 1, 2010, https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2010/scale-economies-in-banking-and-financial-regulatory-reform.

[24]. Allen Berger, William Hunter, and Stephen Timme, “The efficiency of financial institutions: A review and preview of research past, present, and future,” Journal of Banking and Finance 17, no. 2-3 (1993), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/037842669390030H.

[25]. U.S. Census Bureau, Statistics of U.S. Businesses (U.S. & states, 6-digit NAICS), accessed November 9, 2023, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/econ/susb/2017-susb-annual.html.

[26]. Ibid.

[27]. Ibid.

[28]. “McFadden Act of 1927,” Federal Reserve History, November 22, 2013, https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/mcfadden-act.

[29]. Ibid.

[30]. Ibid.

[31]. Atkinson and Lind, Big is Beautiful.

[32]. Ibid.

[33]. Ahmet Ali Taskin and First Yaman, “The effect of branching deregulation on finance wage premium” (FAU Discussion Papers in Economics, August 2023), https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/280992/1/1876291222.pdf.

[34]. White House, Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy, July 9, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/07/09/executive-order-on-promoting-competition-in-the-american-economy/.

[35]. “U.S. Bank M&A to Remain Stalled Until Regulatory, Valuation Headwinds Abate,” Fitch Ratings, July 17, 2023, https://www.fitchratings.com/research/banks/us-bank-m-a-to-remain-stalled-until-regulatory-valuation-headwinds-abate-17-07-2023.

[36]. Barry Lynn, “Antitrust: A Missing Key to Prosperity, opportunity, and Democracy,” Desmos, October 2013, https://d1y8sb8igg2f8e.cloudfront.net/documents/Antitrust.pdf.

[37]. Atkinson and Lind, Big is Beautiful.

[38]. James Fontanella-Khan, Ortenca Aliaj, and Rob Armstrong, “M&T Bank to buy People’s United Financial in $7.6bn deal,” Financial Times, February 22, 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/b18c4600-aea2-47f6-8ba1-2e5be7bb4c14.

[39]. U.S. Census Bureau, Statistics of U.S. Businesses (U.S. & states, 6-digit NAICS), accessed November 9, 2023, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/econ/susb/2017-susb-annual.html.

[40]. Ibid.

[41]. Atkinson and Lind, Big is Beautiful.

[42]. Ibid.

[43]. Laurence Baker, M. Kate Bundorf, and Anne Beeson Royalty, “The Effects of Multispecialty Group Practice on Healthcare Spending and Use” (working paper, NBER, June 2019), https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w25915/w25915.pdf.

[44]. Robert Miller et al., “The Value of Electronic health Records in Solo or Small Group Practices,” Health Affairs 24, no. 5 (2005), https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.24.5.1127.

[45]. Baker, Bundorf, and Beeson Royalty, “The Effects of Multispecialty Group Practice on Healthcare Spending and Use.”

[46]. U.S. Census Bureau, Statistics of U.S. Businesses (U.S. & states, 6-digit NAICS), accessed November 9, 2023, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/econ/susb/2017-susb-annual.html.

[47]. Ibid.

[48]. Maureen Ohlhausen, “Certificate of Need Laws: A Prescription for Higher Costs,” Antitrust 30, no. 1 (Fall 2015), https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_statements/896453/1512fall15-ohlhausenc.pdf.

[49]. Jessica Harris, “Certificate of need Laws: A Brief History,” Cardinal Institute for West Virginia Policy, https://cardinalinstitute.com/certificate-of-need-laws-a-brief-history/.

[50]. Ohlhausen, “Certificate of Need Laws: A Prescription for Higher Costs”; Adney Rakotoniaina and Johanna Butler, “50-State Scan of State Certificate-of-Need Programs,” National Academy for State Health Policy, May 22, 2020, https://nashp.org/state-tracker/50-state-scan-of-state-certificate-of-need-programs/.

[51]. Ohlhausen, “Certificate of Need Laws: A Prescription for Higher Costs.”

[52]. Ibid.

[53]. Arielle Dreher, “States look to crack down on health care merger,” Axios, June 26, 2023, https://www.axios.com/2023/06/26/states-look-health-care-mergers.

[54]. Ibid.

[55]. “A Tool for States to Address Health Care Consolidation: Improved Oversight of Health Care Provider Mergers,” National Academy for State Health Policy, November 12, 2021, https://nashp.org/a-tool-for-states-to-address-health-care-consolidation-improved-oversight-of-health-care-provider-mergers/.

[56]. Reed Abelson, “Corporate Giants Buy Up Primary Care Practices at Rapid Pace,” The New York Times, May 8, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/08/health/primary-care-doctors-consolidation.html.

[57]. Alan Condon, “Corporate giants ramp up primary care deals,” Hospital CFO Report, May 8, 2023, https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/finance/corporate-giants-ramp-up-primary-care-deals.html#:~:text=U.S.%20Sen.,patients%20and%20increasing%20healthcare%20costs.%22.

[58]. U.S. Census Bureau, Statistics of U.S. Businesses (U.S. & states, 6-digit NAICS), accessed November 9, 2023, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/econ/susb/2017-susb-annual.html.

[59]. Ibid.

[60]. Maria João Ribeirinho et al., “The Next Normal in Construction,” McKinsey & Company, June 2020, https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Capital Projects and Infrastructure/Our Insights/The next normal in construction/The-next-normal-in-construction.pdf.

[61]. Ibid.

[62]. Tooey Courtemanche, “Why efficiency in construction is a global issue,” Independent, October 6, 2021, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/business-reporter/efficiency-construction-global-issue-b1929129.html.

[63]. Santiago Castagnino et al., “How to Nail M&A in Engineering and Construction,” BCG, December 19, 2019, https://www.bcg.com/publications/2019/engineering-construction-mergers-acquisitions.

[64]. U.S. Census Bureau, Statistics of U.S. Businesses (U.S. & states, 6-digit NAICS), accessed November 9, 2023, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/econ/susb/2017-susb-annual.html.

[65]. Ibid.

[66]. Ibid.

[67]. Ibid.

[68]. Ibid.

[69]. “The Development of Our Building Codes,” California Real Estate Inspection Association, https://www.creia.org/the-development-of-our-building-codes.

[70]. Ibid.

[71]. Barry LePatner, Broken Buildings, Busted Budgets: How to Fix America’s Trillion-Dollar Construction (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2007).

[72]. Ibid.

[74]. LePatner, Broken Buildings, Busted Budgets: How to Fix America’s Trillion-Dollar Construction.

[75]. “Chapter 19-50 State Summary Mechanic’s Lien Law,” Fullerton and Knowles, 2019, https://fullertonlaw.com/50-state-summary-mechanics-lien-law#_Toc10973296.

[76]. LePatner, Broken Buildings, Busted Budgets: How to Fix America’s Trillion-Dollar Construction.

[77]. “How IT Can Help Fix America’s Ailing Construction Industry” (ITIF, January 2008), https://itif.org/events/2008/01/24/how-it-can-help-fix-america%E2%80%99s-ailing-construction-industry/.

[78]. U.S. Census Bureau, Statistics of U.S. Businesses (U.S. & states, 6-digit NAICS), accessed November 9, 2023, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/econ/susb/2017-susb-annual.html.

[79]. Ibid.

[80]. “It’s Not Just About Costs Per Acre, Even in Tight Times,” Purdue University, April 6, 2015, https://ag.purdue.edu/commercialag/home/resource/2015/04/its-not-just-about-costs-per-acre-even-in-tight-times/.

[81]. Catherine Paul et al., “Scale Economies and Efficiency in U.S. Agriculture: Are Traditional Farms History?” Journal of Productivity Analysis 22 (2004), https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11123-004-7573-1.

[82]. James MacDonald, Robert Hoppe, and Doris Newton, “Three Decades of Consolidation in U.S. Agriculture” (technical paper, United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, March 2018), https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/88057/eib-189.pdf.

[83]. Ibid.

[84]. Ibid.

[85]. Edward Lotterman, “Farm Bills and Farmers: the effects of subsidies over time,” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, December 1, 1996, https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/1996/farm-bills-and-farmers-the-effects-of-subsidies-over-time.

[86]. Ibid.

[87]. Dennis Jansen, Liqun Liu, and Andrew Rettenmaier, “U.S. Farm Subsidies: A Prime Example of Crony Capitalism,” Private Enterprise Research Center, July 29, 2021, https://perc.tamu.edu/PERC-Blog/PERC-Blog/U-S-Farm-Subsidies-A-Prime-Example-of-Crony-Capita.

[88]. Chris Edwards, “Cutting Federal Farm Subsidies” (Cato Institute, August 2023), https://www.cato.org/briefing-paper/cutting-federal-farm-subsidies#types-farm-subsidy.

[89]. Anne Schechinger, “One-third of all crop insurance subsidies flow to massive insurance companies and agents, not farmers,” EWG, July 12, 2023, https://www.ewg.org/research/one-third-all-crop-insurance-subsidies-flow-massive-insurance-companies-and-agents-not; Chris Edwards, “Farm Bill 2023: Crop Insurance Subsidies” (Cato Institute, July 2023), https://www.cato.org/blog/farm-bill-2023-crop-insurance-subsidies.

[90]. Ibid.

[91]. Congressional Budget Office, “USDA Farm Programs” (Washington, D.C.: May 2023), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2023-05/51317-2023-05-usda_0.pdf.

[92]. Ibid.

[93]. Jansen, Liu, and Rettenmaier, “U.S. Farm Subsidies: A Prime Example of Crony Capitalism.”

[94]. Ibid.

[95]. United States Department of Agriculture, Farm and Land in Farms 2021 Summary (Washington, D.C.: February 2022), https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/Todays_Reports/reports/fnlo0222.pdf.

[96]. Ibid.

[97]. “Food and Agricultural Policy: Taking Stock for the New Century” (technical paper, U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2001), https://ntrl.ntis.gov/NTRL/dashboard/searchResults/titleDetail/PB2002105128.xhtml.

[98]. Michael Duffy, “Economies of Size in Production Agriculture,” Journal of Hunger and Environmental 4, no. 3-4 (2009), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3489134/#R1.

[99]. Author’s calculations. United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Resource Management Survey (ARMS) (government payments and crop sales), accessed January 17, 2024, https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/arms-farm-financial-and-crop-production-practices/.

[100]. Ibid.

[101]. “Economics of Broadband Networks: An overview,” NTIA, March 2022, https://broadbandusa.ntia.doc.gov/sites/default/files/2022-03/Economics%20of%20Broadband%20Networks%20PDF.pdf.

[102]. U.S. Census Bureau, Statistics of U.S. Businesses (U.S. & states, 6-digit NAICS), accessed November 9, 2023, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/econ/susb/2017-susb-annual.html.

[103]. Ibid.

[104]. Ibid.

[105]. “High Cost Loop,” Universal Service Administrative Co., https://www.usac.org/high-cost/funds/legacy-funds/high-cost-loop/.

[106]. U.S. Census Bureau, Statistics of U.S. Businesses (U.S. & states, 6-digit NAICS), accessed November 9, 2023, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/econ/susb/2017-susb-annual.html.

[107]. Ibid.

[108]. Ibid.

[109]. Ted Bolema, “Decoding the 2023 FTC and DOJ Merger Guidelines: Insights into Shifting Antitrust Enforcement” (Mercatus Center, February 2024), https://www.mercatus.org/research/policy-briefs/decoding-2023-ftc-and-doj-merger-guidelines-insights-shifting-antitrust.

[110]. Harry Robins et al., “New HSR Form Will Transform the U.S. Merger Review Process,” Morgan Lewis, June 30, 2023, https://www.morganlewis.com/pubs/2023/06/new-hsr-form-will-transform-the-us-merger-review-process.